Guest author: Stuart Clenaghan

In my view there is a critical missing link in REDD+ thinking, and that relates to the high cost of finance for small and medium-sized enterprises (SME) in developing countries. SMEs are widely acknowledged to be the real engines of economic growth, and account for between 80 per cent and 90 per cent of forest enterprises. Yet SMEs face strong headwinds when it comes to accessing funding. For many SMEs, the unsustainable exploitation of natural resources – or “natural capital” – is a substitute for financial capital.

This perspective draws upon insights gained as a co-founder of a private sector sustainable forestry company, striving to deliver strong financial, social and environmental results in Peru (a UN-REDD Programme partner country), as well as my experience of capital markets as a former investment banker.

The link between the high cost of capital for the private sector in developing economies and the unsustainable exploitation of the natural capital of forests has received little attention in the global debate on REDD+.

Yet the behaviour of the private sector is fundamentally influenced by the availability of finance – both equity investment and loans – and by how much it costs. This is as true for a farmer working a two-hectare plot as it is for a forestry company working two hundred thousand hectares. Where capital is expensive, or difficult to obtain, the only option for many is to turn to the exploitation of natural capital. Conversely, where cheap finance targets forest-friendly enterprise, business follows.

For REDD+ to succeed we must overcome the shortcomings of financial markets in countries where forests are at risk. And because the drivers of deforestation are rooted in the wider economy (think charcoal supply chains, or urban markets for agricultural produce), investment is needed not just in forests, but in other areas too. Anyone with experience in building businesses in developing economies will attest to the difficulties in raising money. Equity investment is often tightly controlled by wealthy elites, and there are few other sources of venture capital or private equity. Bank loans are expensive, frequently at rates of 15-20% or more, available only to those offering guarantees and collateral. Additionally, businesses in poorer countries face costs that peers in developed markets do not have. True, labour bills are generally lower, but poor infrastructure and lack of service providers force companies to invest in vertically integrating their operations. One company, a 5,000 hectare rice farm in east Africa, has had to build its own hydro and biomass power plants, construct rice drying polishing facilities, invest in packaging and marketing, and on top of that maintain a 100 kilometre stretch of road. This expenditure would be unnecessary had it been a potato farm in eastern England, where outsourced services are readily available.

It is hardly surprising, then, that some turn to the exploitation of natural capital. We can see examples across the globe, from East Africa’s charcoal trade (estimated to be worth US$ 350 million a year in Dar es Salaam alone and employing hundreds of thousands of people), to the destruction of mangroves in India for shrimp farming, and agricultural frontiers where forest is cleared for ranching or crops.

Historically, the transformation of natural capital to financial capital has underpinned the growth of some of today’s biggest economies. Waves of deforestation in England fed agricultural expansion, maritime trade and the early industrial revolution. The great Hanseatic port cities of Germany and the Baltic expanded on the back of trade of timber pulled from northern hinterlands. Indeed, the very foundations of monetary systems were built upon natural capital – the world’s first coins were forged in Lydia (in today’s western Turkey) from bronze and silver smelted with charcoal from deforested uplands.

To achieve lasting REDD+ results, access to financial capital must replace the exploitation of natural capital. We need more than investment in forests: we need to effect deep-rooted socio-economic changes across whole economies. If we ask forest nations to do a job in protecting forests and sinking carbon, then we must provide financial capital for sustainable growth.

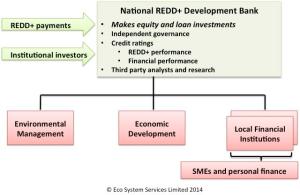

By linking financial capital, economic development, and the goals of REDD+ we can gain insight into the type of mechanism required:

- First, countries that deliver reduced emissions – or even carbon sinks – need to be paid for results at agreed prices, and on a bilateral basis. Market-priced payments introduce too much uncertainty and income volatility. And, as we have seen with the much-criticised Clean Development Mechanism, project-based accreditation brings high transaction costs, uncertain financing and drains scarce management resources.

- Second, forest nations need national development banks that supply low-cost finance – equity and loans – to spur REDD+-friendly private sector enterprise from micro-scale to national-sized corporations. As a model, take a look at Brazil’s BNDES, or even Germany’s KfW (set up to support post-war reconstruction).

- Third, result-based payments must be ring-fenced for REDD+. The more successfully a country reduces emissions the more it earns, and the more capital it has to invest. REDD+ benefits will show up throughout the economy and that should be incentive for countries to adopt a holistic strategy. In fact, many governments have already started to identify where investment is needed in REDD+ Readiness plans produced with the UN-REDD Programme and Forest Carbon Partnership Facility.

Two interesting outcomes might result from such arrangements:

- The first is that REDD+ development banks could operate at a profit – REDD+ investment can make money.

- The second is that ring-fenced REDD+ payments could enable countries to enhance their creditworthiness and issue bonds. In other words, a lot more private investment capital could be leveraged into REDD+.

Deforestation is driven by economic factors. For sure we need better land rights, governance, enforcement and conservation. But at the heart of the matter is the challenge of achieving non-extractive sustainable growth in forest nations. That can only happen if REDD+ bridges the deficiencies of financial markets.

Bio: Stuart Clenaghan is an investor in environmental and sustainable forestry businesses. In 2008, he co-founded Green Gold Forestry, an FSC-certified sustainable forestry company operating in Peru, producing sawn hardwoods. Alongside its 154,000ha of forest concessions, GGF also sources logs through its programme of community forestry partnerships. His consultancy, Eco System Services Limited, specialises in developing financing models for large-scale land-use projects. He is also a senior fellow of the Climate Bonds Initiative and a trustee of Botanic Gardens Conservation International, and a former investment banker with Lehman Brothers and UBS.

Bio: Stuart Clenaghan is an investor in environmental and sustainable forestry businesses. In 2008, he co-founded Green Gold Forestry, an FSC-certified sustainable forestry company operating in Peru, producing sawn hardwoods. Alongside its 154,000ha of forest concessions, GGF also sources logs through its programme of community forestry partnerships. His consultancy, Eco System Services Limited, specialises in developing financing models for large-scale land-use projects. He is also a senior fellow of the Climate Bonds Initiative and a trustee of Botanic Gardens Conservation International, and a former investment banker with Lehman Brothers and UBS.

FAO Forestry Department RSS feed

FAO Forestry Department RSS feed

Leave a comment

Comments feed for this article